[ad_1]

Had there ever been a collection of individual superstars like those assembled by Real Madrid in 2003? When David Beckham arrived from Manchester United that summer, he joined Ronaldo, Zinedine Zidane, Luis Figo, Roberto Carlos and Raul.

All six players had featured among the top two in the voting for the Ballon d’Or in the previous four years. For context, there is currently no club in the world that can claim to employ more than one player to have achieved that in the last four years.

The so-called Galacticos had been unable to defend their Champions League crown in the 2002/03 season, despite a famous Ronaldo-inspired win over Manchester United in the quarter-final. But they did win La Liga and were expected to do so again.

What would unfold was Madrid’s first trophyless season since 1995/96. That ignominious campaign brought no European football for the first time in a generation amid turmoil off the pitch. This was more shocking in its own way. It was thought impossible.

And yet, club president Florentino Perez saw his plans unravel. Two thirds of the way into the season, the team were top of La Liga and expecting glory in Europe but endured a collapse that left his policy under scrutiny and the Galacticos a byword for excess.

As Madrid faltered, Valencia fired.

It was they who reclaimed the title under Rafa Benitez and won the UEFA Cup to go with it. They were a brilliant team but did not boast even a single Ballon d’Or podium-maker. For Benitez, the devil was in the detail. For Valencia, the strength was in their unity.

Xisco Munoz made his Valencia debut that season, appearing 33 times in all competitions. “Until then, I had only played for myself,” he tells Sky Sports. “Maybe not myself but my own characteristics. Rafa started giving me different ideas about the game.”

He explains: “Real Madrid had the top players in the world. We only had one way to beat them. More teamwork, more power, more concentration, more fight. We had to have better values. That is something that Rafa taught us on and off the pitch.”

That Valencia team responded with one of the great European seasons. “I feel everybody had it in their blood. We had that winning mentality. You can lose games. That is one thing. But when you have it in the blood to win, win, and win again, anything is possible.”

Amid the hoopla surrounding Beckham’s signature, Real Madrid lost some of their winners that summer. The departure of long-time leader Fernando Hierro was understandable given his age but Steve McManaman, Fernando Morientes and Claude Makelele left too.

The quartet had made a combined 131 appearances in the previous season – a lot of minutes that needed to be replaced. Beckham was wedged in as a central midfielder but despite his qualities he was no like-for-like replacement for the pivotal Makelele.

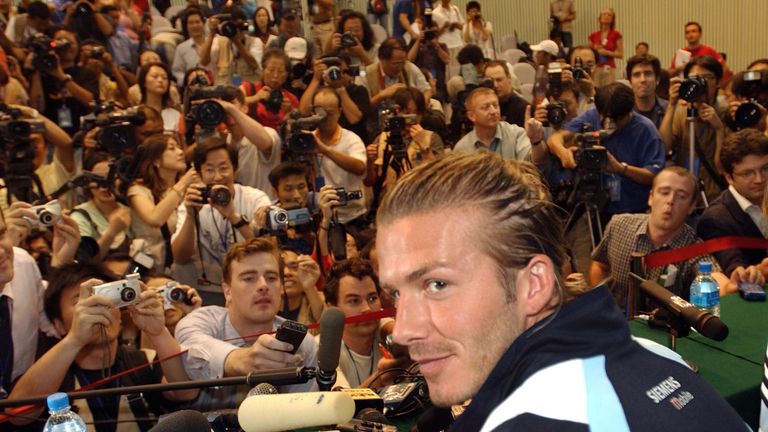

Zidane’s famous quip asking why anyone would put another layer of gold paint on a Bentley while losing the engine would come to sum up this entire era. But his words came against the backdrop of a money-spinning tour of Asia with Beckham-mania at its peak.

There were exhibition matches in Beijing, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Bangkok, giddy excitement that these Real Madrid players now transcended football. The man expected to fashion them into a team was Carlos Queiroz, brought in from Manchester United.

The power dynamic was an unusual one.

For Jose Peseiro, the newly-appointed assistant to Queiroz, it was an experience just to be in the room with these players. “I had been a player in the second division,” Peseiro tells Sky Sports. “I had never before shared a dressing room with such big players.”

Peseiro insists that it was not as awkward as he had feared. “It was a fantastic experience for me to get to understand them. People think it is not easy to train Beckham, Figo, Ronaldo and Zidane. But it is not difficult because they are smart guys,” he says.

“Of course, they do not do the same things that you would expect from a smaller team. At a smaller team, the players eat together more, speak more, connect more, it is like a family. There, no. They live more of an individual lifestyle, they do not share so much.

“Different egos, different personalities, a coach must manage it well. But in the games, they always did the maximum. I do not say it is easy to command this kind of team but I will not say it is hard because they want to play, they want to enjoy the game.”

Benitez saw the team ethos very differently.

“When we had the meetings with him, he was always so clear about it,” recalls Xisco. This was a coach who recognised the importance of sacrifice. “I know your strengths are attacking but maybe the team needs you to give me the things you do not like.”

Valencia had quality players. Benitez turned them into players who gave everything for the team. “Sometimes it is perfect if you are attacking and the game is the way you like it,” adds Xisco. “But if you have balance and are willing to defend too, that is the best way.”

At the end of February, it did not look likely to be enough. Madrid had powered past Celta Vigo with goals from Ronaldo, Zidane and Figo. Valencia were beaten by Espanyol. It left them eight points behind the Galacticos with a dozen games left to play.

With both clubs still in their respective European competitions, it was all set for the defining stage of the season – and this was where the big-game players of Madrid were expected to step up. But there was a problem. Injuries and fatigue were taking their toll.

“The project was in the mind of Florentino Perez, this idea of ‘Zidanes y Pavons’,” explains Peseiro. The superstar signings would be balanced out by trusting in the young talent from the club’s famed academy, with Francisco Pavon as the poster boy for the policy.

Having baulked at paying Makelele more money, Perez’s plan hinged on these young players filling out the squad for a fraction of the cost. But Pavon and Raul Bravo struggled in defence, while young forward Javier Portillo scored only twice in 30 appearances.

“At that moment, we had 11 good players and then the others,” says Peseiro. “Makelele, Morientes, McManaman, they had been very good. The problem was that when we needed to put players from the bench, from the academy, into the team, it was not so good.”

Humiliatingly for Perez, it was Morientes, loaned out to Monaco, who ended their European ambitions that season, scoring home and away against Madrid to knock them out of the Champions League. He would go on to finish as the competition’s top scorer.

Broken by that defeat to Monaco, the team would lose 3-0 at home to Osasuna next time out in La Liga. Still top at that stage, Madrid, astonishingly, would go on to lose their final five matches of the season, eventually finishing fourth in the table. A collapse.

All sorts of criticism came, Queiroz paying with his job and attitudes being questioned. Twenty years on, it seems fairer to point out that the physical demands may have been too taxing. Zidane and Figo were the wrong side of 30 but could never be left out.

“Many times they played fantastic football,” says Peseiro “Everyone enjoyed it. Even me on the bench. But there came a time when some players needed a rest and the second option for those positions was not so good. We just could not keep the same level.”

When the going got tough, Valencia got going. Ten games unbeaten, eight won, were enough to secure the title with two games to spare. They lost their last two games of the La Liga season but only because attention shifted to Europe. They won the UEFA Cup.

Vicente and Mista scored the goals that beat Marseille in Gothenburg, having been the team’s top scorers in La Liga too. The names were not as stellar as those of Madrid but it was a squad packed with Valencia legends. “Excellent players,” says Xisco.

“We had Pablo Aimar, Santi Canizares…big players. But they were big players because every day in training they had the ability to concentrate, to be ready every day, to give 100 per cent in every session. That pushes you to give 100 per cent too.”

It is a parable for the importance of the team.

“Talent is always good, always very nice,” concludes Xisco. “But I learned in those years that nobody in life is going to give you anything for free. I became addicted to hard work. Because the lesson is that you have to work hard for what you want.”

Get Sky Sports on WhatsApp!

You can now start receiving messages and alerts for the latest breaking sports news, analysis, in-depth features and videos from our dedicated WhatsApp channel!

Find out more here…

[ad_2]

Source link